Barbara BloomThe Weather

–

Cancelled

–

This exhibition has regrettably been cancelled due to COVID19 restrictions.

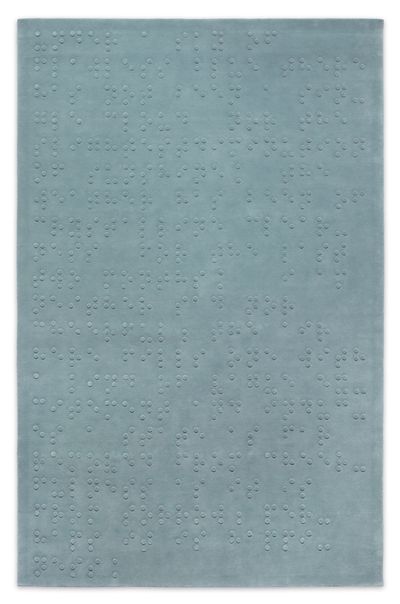

In Barbara Bloom’s The Weather, a series of carpets hover on platforms at various heights above the floor, each in a different hue or shade of blue, green and grey reminiscent of clouds and sky, or pools of water. Upon each carpet, texts in braille present descriptions of atmospheric conditions taken from a wide range of sources, including Raymond Chandler, André Gide, James Joyce, Gabriel García Márquez, Cormac McCarthy, Haruki Murakami and Daphne Du Maurier, as well as weather statistics for Los Angeles on 11 July 1951 at 2:00am (the place and date of birth of the artist). The work accentuates the complexity and melancholy aspects of ‘reading’ – the blind is unable to see what is being described, and the sighted cannot read the braille. The walls are partially painted with an elusive grey color (somewhere between a shade and a hue), creating a sensation vaguely reminiscent of flying above the clouds, unable to see land through the mist, or being partially submerged in a fictitious sea.

Alongside this installation, the exhibition presents selections from Bloom’s series Works for the Blind. Each of the works contains a text about the nature of seeing. Here, the textual component of the work appears twice, once in braille typed over an image, and once as the size of a postage stamp, printed white on black in miniscule types below. Accompanying each of these captions is a photograph of an illusion; a magician levitating a matchbook, a UFO landing, an egg floating in midair. In this series of works, sighted people can see the illusionary photograph (though not how the illusion is accomplished), but most will only be able to squint and guess at the message conveyed by the too-small text. The blind will be able to read the text (the plexiglass has been cut away over the braille, allowing it to be touched), but unable to see the photograph. The gap in understanding between the visual and the textual that Bloom explores in The Weather delves into the difficulties of seeing things for what they are.

"Under a sky of flawless blue; during the twelve days … there has not been a single cloud nor the slightest diminution of sunshine … the weather has been of crystalline clearness for the last two months. I am neither sad nor cheerful; the air here fills one with a kind of vague excitement and induces a state as far removed from cheerfulness as it is from sorrow; perhaps it is happiness."

— André Gide, The Immoralist

(Vintage International, 1996)

Reproduced in braille upon a field of aquamarine, the passage is excerpted from a 1921 novel which follows a narrator, Michel, accompanied by his wife, on a vacation from their native France to Tunis. Upon falling seriously ill with tuberculosis, he (with the aid of his wife) befriends various children, all male. At first portrayed as a sort of exotic fascination with the boys, in line with a colonial fetishization of the times, "his hair is shaved in Arab fashion … The gandoura, sliding down, reveals his delicate shoulder. I must touch it …," Michel’s obsessions are explained to the reader as a longing for health. From his sickbed, the narrator speaks of the first boy, "…his tongue was pink as a cat’s. How healthy he was! That was what beguiled me about him: health. The health of that little body was beautiful." The flawlessness of the sky in the passage selected by Bloom for The Weather,– unravaged by age, a symbol of youth – recurs throughout the novel. It is what appears to follow our protagonist, whose tale of illness is a thin veil over the reality of his moral transgressions. What we are reading are accounts of victims, as told by the unreliable narrator: the tubercular paedophile himself.

The inaccessibility of Bloom’s quotations function as a sort of prop, or set design, of misreading. The relationship to literature is not so much fictitious (the braille transcriptions are, indeed, accurate) as it is unpredictable (field of blue that infer a remote meaning). No different perhaps than a weather report, where facts mean nothing. How do you measure a subjective understanding of a particular gust of wind (imagine the spouse at a gravestone, the magician in the park balancing a deck of cards), of a violent storm (the sea captain, the farmers praying for an end to the drought), of the sparkle of falling snow (the automobile pulling over on the highway, the child catching flakes on their tongue)?

"All the sky to the north had darkened and the spare terrain they trod had turned a neuter grey as far as the eye could see … The storm front towered above and the wind was cool … Shrouded in the black thunderheads the distant lightning glowed mutely like welding seen through foundry smoke. As if repairs were underway at some flawed place in the iron dark of the world."

— Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses

(Vintage International, 1993)

The iron dark of the world. That molten, primordial centre of the earth. Dormant sites, awaiting the eruption, still exist across our landscape. The weather is one of the most mundane sensations that connects us all. Experienced in a museum setting, the vivid portrayals of weather bring the outside in.

Do you dare to look?

Supported by